River Guides: Elke Littleleaf and Alysia Littleleaf (Credit: Brian Burk)

The Damned Deschutes

People who love an iconic Oregon river say an electric utility is harming it.

By Nigel Jaquiss, Oregon Journalism Project

December 18, 2024

MAUPIN, Ore. — Alysia Littleleaf and her husband, Elke, make their living as fishing guides on the lower Deschutes River, near the Warm Springs Reservation.

A major tributary of the Columbia River, the Deschutes irrigates farmland, generates electricity, and is the lifeblood of Central Oregon’s biggest industry, tourism. The river and its high desert landscape epitomize the region’s rugged beauty. Visitors come to raft, hike, bike, camp and fish on what legendary Oregon outdoors writer Harry Teel once deemed “the finest overall fly-fishing river in western America.”

Yet the Littleleafs, along with other guides, fishermen and environmentalists, have marshaled evidence that the river today is ailing—and getting worse.

“The fish in the Deschutes have been very significant to our people for time immemorial,” says Alysia Littleleaf, 40, a member of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. “They can’t speak for themselves, of course, but if they could, I think they’d say, ‘I’m sick. I’m barely here.’”

Data collected by the nonprofit Deschutes River Alliance shows that two key indicators of aquatic health—water temperature and pH—regularly exceed Oregon Department of Environmental Quality guidelines for the river. Over the past 12 years, for instance, the DRA measurements show the water has been too warm on 297 days and, over the past eight years, it has exceeded the pH standard 75% of the time. Meanwhile, dissolved oxygen is regularly lower than required.

The result, according to Elke Littleleaf, 56, is noticeable: “I have been fishing the river for 48 years. I’ve noticed the changes,” he says. “There are fewer fish, and we’ve seen algal growth like we never had before.”

Littleleaf says he and his wife used to donate excess catch to tribal elders, but many fish now suffer from parasite-borne black spot disease, so they’ve stopped doing that.

The Littleleafs and other critics blame the lower Deschutes’ ills on the state’s largest utility, Portland General Electric. For more than 60 years, PGE has run the three-dam Pelton-Round Butte hydroelectric complex, which sits about 50 river miles upstream of Maupin and cleaves the lower Deschutes from its tributaries.

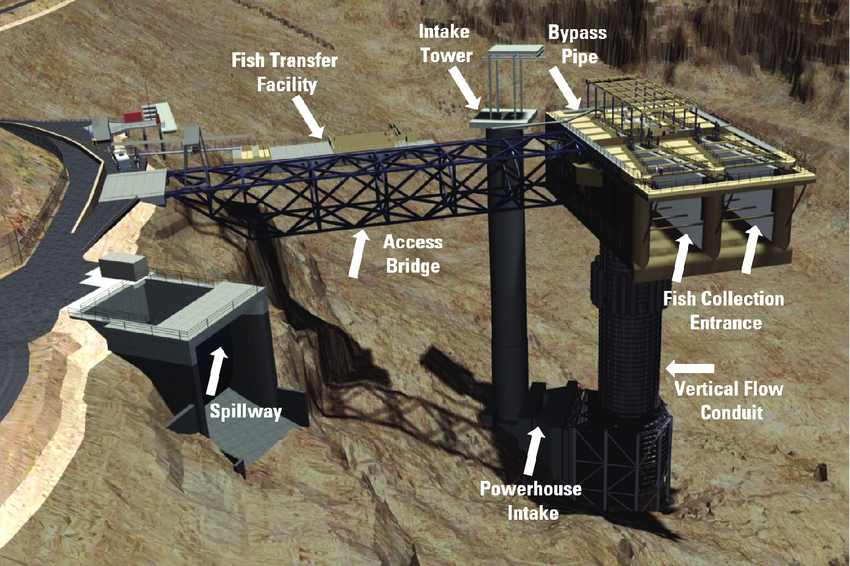

In particular, critics point to a decision PGE and state regulators made 15 years ago. The decision: to install, at ratepayer expense, a device designed to restore the native fish runs that dams blocked.

But critics say the device hasn’t worked and the water quality in the lower Deschutes has deteriorated because of it. One of them is Carol Beatty, the mayor of Maupin, the unofficial capital of the lower Deschutes.

“The Deschutes River is what brought my husband and me to Maupin nearly 30 years ago,” she says.

Beatty, 81, says conditions have changed. “There’s a lot more algae along the river, and the fishing isn’t as good. What PGE’s done with the dams caused that,” says Beatty, who for many years taught women how to row the river and estimates she’s rafted it more than 200 times.

PGE acknowledges that 15 years after it began operating what’s called the selective water withdrawal tower, it has not yet worked as hoped. But the utility says critics are exaggerating harms to the Deschutes and adds that PGE is “fully in compliance with our license and water quality certificates on the Deschutes.”

The issue has divided people in the Deschutes River Basin. On one side: the utility and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, who share ownership of the three-dam complex and jointly defend the tower.

On the other side: the DRA, fishermen, and some residents of the Warm Springs Reservation, such as the Littleleafs. They know the tower exists so PGE can continue to operate the dams. The dams in turn are a crucial cog in Oregon’s drive to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by relying more on hydroelectricity and other forms of renewable energy. But the consequence is that the Deschutes, its fish, and the people who revere them risk becoming collateral damage. Put another way, Oregonians who benefit from reduced greenhouse emissions, including PGE’s 934,000 customers, are inadvertently facilitating the degradation of an iconic waterway.

Big Blender: The selective water withdrawal tower (Credit: Portland General Electric)

Tall Tower: The structure rises 270 feet from the bottom of Lake Billy Chinook (Credit: Portland General Electric)

Unsightly: Black spot disease (Credit: Amy Hazel)

Rick Hafele (Credit: Brian Burk)

The health of the fish runs on the Deschutes has been an issue since the Pelton Dam was completed in 1958. In 1964, with the completion of the Round Butte Dam, PGE unveiled the world’s longest fish ladder. But it never worked and PGE abandoned it four years later.

In the late 1990s, as PGE moved toward renewing the dams’ licenses with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the Warm Springs Tribe announced it wanted the dams for itself.

The tribe’s rationale: The river and the dams are partially on the Warm Springs Reservation, and the dams’ construction harmed a fishery central to the tribe’s culture. (The dams also produce enough electricity to serve about 150,000 homes.)

PGE struck a compromise and agreed to sell the tribe what is now a 49.9% share of the dams, at a heavily discounted price. (The tribe will increase its stake to a majority in 2037.) PGE buys Warm Springs’ share of the electricity, providing the tribe its biggest source of revenue. In 2023, according to PGE’s federal filings, that payment was $47.3 million.

In 2005, FERC granted the dams a new 50-year license on the condition that PGE and the Warm Springs work to restore the passage of native Chinook and sockeye salmon and steelhead trout.

To do that, PGE proposed a novel solution: a selective water withdrawal tower. The tower was supposed to accomplish two things. First, machinery at the top of the tower would generate currents to attract juvenile fish hatched above the dams. They could then be collected and trucked around the dams to the lower Deschutes. (Previously, juvenile fish got lost in the reservoir of Lake Billy Chinook.)

Second, instead of exclusively releasing cold, clear water from the bottom of the reservoir to the lower river as PGE had done since the dams were built, the tower would blend bottom water with warmer surface water.

By releasing a mixture of bottom and surface water, PGE hoped to replicate the natural conditions of the river as if there were no dams.

Although it was an untested technology, the feds approved it. PGE then went in 2008 to the Oregon Public Utility Commission and asked that ratepayers pay the tower’s $107 million cost, plus a profit for the utility.

PGE made the case that ratepayers should foot the bill—whether the tower worked or not.

Records show PUC staff pushed back. So did the Citizens’ Utility Board, a watchdog group. But the three governor-appointed commissioners ultimately bought the utility’s argument (see sidebar, “The Public Utility Commission”).

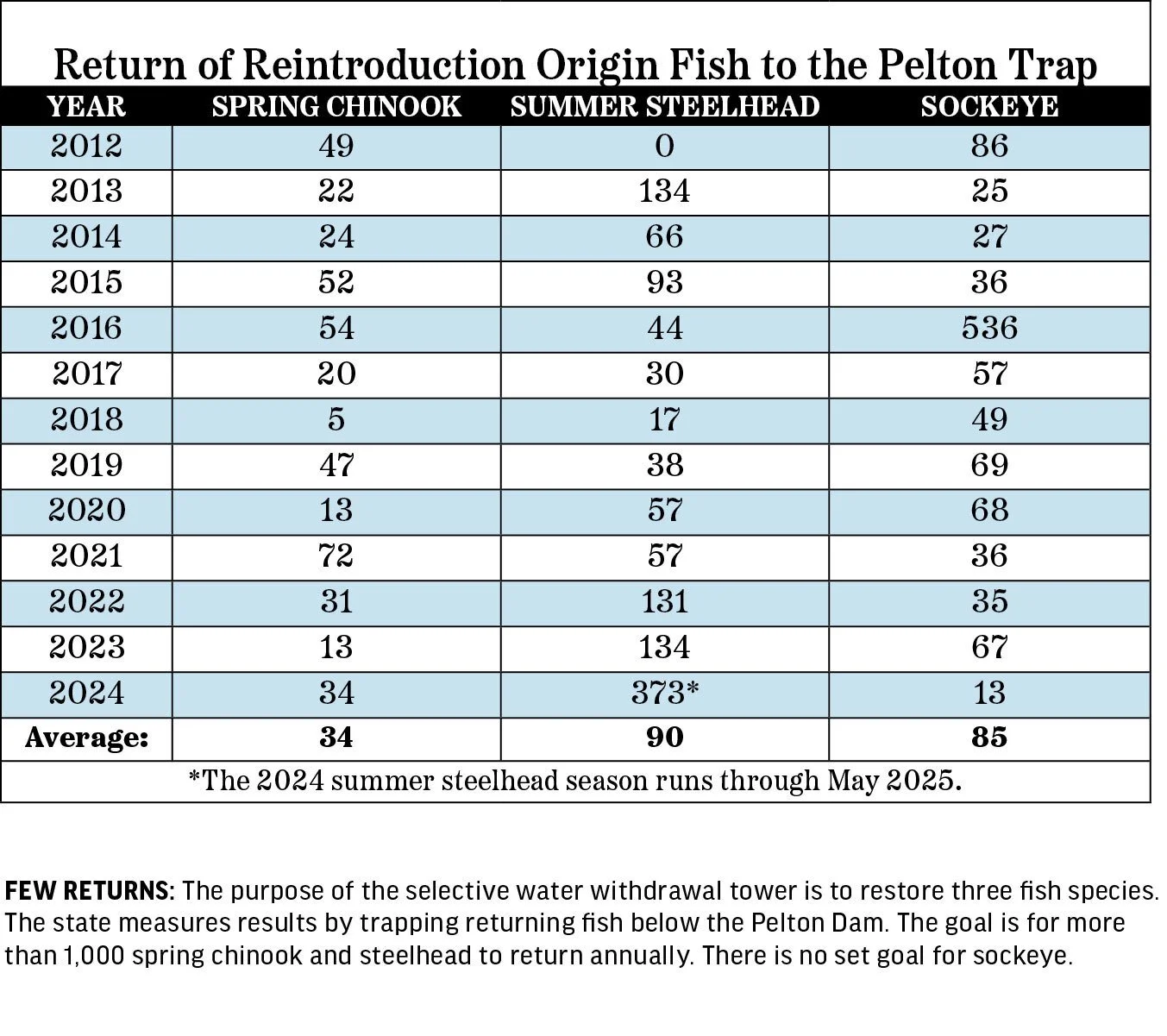

(Source: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife)

Rick Hafele, a retired Department of Environmental Quality scientist who has fished and studied the Deschutes for 50 years, says there was a specific moment when the river’s fortunes changed for the worse: “right after the tower started operating.”

Almost immediately, those who fished the river’s lower 100 miles noticed a difference. “They were complaining about temperature—how warm the water was,” Hafele recalls.

For 22 years, Hafele had worked all over Oregon’s rivers and lakes as a DEQ water quality scientist. And for 35 years, he also moonlighted teaching fishermen about insects and fly-fishing in Maupin. He has written eight books on those subjects.

Hafele and two other retired state scientists (one from DEQ and another from the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife) soon began systematically testing the water for the Deschutes River Alliance and have continued for more than a decade.

They found the water PGE blended and released to the lower river consistently failed to meet the required standards in the utility’s original DEQ permit.

That’s because the warmer water on top came from the Crooked River and the upper Deschutes, which are warmer and more polluted than the Metolius River, the dams’ third tributary.

Steve Pribyl, a retired ODFW biologist who spent his career studying the Deschutes, works closely with Hafele. He says another key benchmark of whether the tower is working—fish counts—yields a clear signal (see chart).

His conclusion? “Reintroduction continues to fail miserably at returning adults,” Pribyl says.

PGE has always said the reintroduction of fish would take time. The utility’s hydro environmental manager, Megan Hill, acknowledges fish returns aren’t what the utility hoped but says this year’s record steelhead numbers are encouraging.

“We were probably optimistic on the time scale,” Hill says. “We’re seeing incremental progress. We want it to be faster.”

From 2010 through 2020, DEQ and PGE negotiated a series of “interim agreements” allowing the utility to meet lower water quality standards than in the original permit. In effect, Hafele says, the state agency gave PGE a pass.

“The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality needs to enforce the Clean Water Act,” Hafele says. “They need to do this by requiring that PGE develop a water quality improvement plan.”

David Moskowitz, executive director of nonprofit The Conservation Angler, agrees. “The health of the lower river is at risk for sure,” Moskowitz says. “DEQ is not looking out for the public’s interest. That agency needs a kick in the pants.”

PGE spokeswoman Allison Dobscha says the interim agreements reflect the “expectation that we would continue to adjust our operations as we gather data, analyze results, and make thoughtful course corrections supported by the science.”

DEQ insists it is holding PGE and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs accountable.

“The Pelton-Round Butte dam project and its facilities are in compliance with their DEQ-issued 401 water quality certification,” says DEQ spokesman Antony Vorobyov.

Vorobyov says by blending the water, the tower achieves the goal of replicating the conditions that would exist without the dams. “The selective water withdrawal tower largely achieves what it was designed to do.”

Dobscha says critics who want PGE to return to releasing as much of the cold, cleaner water from the bottom of Lake Billy Chinook are missing the bigger picture.

“Their persistence on this topic results from a desire to return to the conditions that resulted in predictable patterns for certain fish species that are attractive and exciting for sport fishing over more natural conditions that benefit the broader ecosystem of the Deschutes,” she says.

Runaway River: The Deschutes races 252 miles from the Central Cascades to the Columbia (Credit: Brian Burk)

Gateway Drug: Maupin is the recreation capital of the lower Deschutes (Credit: Brian Burk)

Slim Pickings: Critics say beneficial aquatic insects have declined (Credit: Brian Burk)

Elke Littleleaf and Alysia Littleleaf (Credit: Brian Burk)

To be sure, among the people who would benefit from the removal of the tower are sport fishermen. But since its founding in 2013, the DRA has had one focus—advocating for the lower 100 miles of the river.

In 2016, the group took its fight against the tower to federal court in Portland, suing under the federal Clean Water Act. U.S. District Judge Michael Simon ruled in PGE’s favor, finding the DRA hadn’t proved its case.

The alliance appealed. In 2021, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the case without considering DRA’s complaint, reasoning that the tribe has sovereign immunity and therefore cannot be sued.

Through the years, The Oregonian, Oregon Public Broadcasting and other news outlets have reported on the conflict over the tower. And this year, local filmmakers released a documentary about the lower Deschutes, called The Last 100 Miles. The filmmakers said PGE and the Warm Springs declined interview requests.

The Oregon Journalism Project learned this fall that the tribe hired a public relations firm that pressured some venues, including the Deschutes Brewery and the Patagonia store in Bend, to cancel planned screenings of the film.

“The Tribes are concerned how the documentary undermines their tribal sovereignty,” Mixte Communications of Portland wrote to one venue in a November email. “This documentary is a public relations attempt at circumventing what the host—Deschutes River Alliance—couldn’t accomplish twice through the courts.”

Bobby Brunoe, CEO of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, says critics of the selective water withdrawal tower are myopic and self-interested and lack the tribe’s long-term perspective. “It’s disappointing,” Brunoe says.

“Our work covers the entire Deschutes basin, not just the lower river,” Brunoe adds, noting the tribe has been involved in dozens of different projects to improve habitat and water quantity and quality.

Brunoe acknowledges fish returns have been less than he and others hoped for. “We knew it was going to be a long-term process,” he says. “We're always very patient.”

The disagreement over the tower isn’t exactly David versus Goliath. David at least had a slingshot. Last year, the DRA reported revenues of just $437,000. PGE collects more than that every 90 minutes.

At the same time, some members of the Oregon Legislature are paying attention. Two members of a key panel, the House Committee on Agriculture, Land Use, Natural Resources, and Water, share some of critics’ concerns. One of them, state Rep. Mark Gamba (D-Milwaukie), is among Salem’s strongest advocates for Oregon’s clean energy transition, which depends in part on the flexibility and storage capacity of dams.

Nonetheless, Gamba is skeptical of the tower. “Fish returns above the dam are abysmal, which means that the tower has failed in its purpose,” Gamba says. “Its use should be discontinued.”

Gamba thinks it’s time for neutral parties to do some fact-finding. “The Legislature should start with oversight and get some questions answered by the PUC, DEQ and PGE,” he says.

Gamba’s colleague, Rep. Ken Helm (D-Beaverton), grew up in Bend and says he has camped and fished on the river every year since 1980, one year spending 70 days on the Deschutes. Speaking from personal experience, he’s noticed big changes since PGE erected the tower.

“Algae was of negligible presence prior to the change in temperature regime,” Helm says. “I have also observed the significant decline in insect hatches—salmon flies, mayflies and caddisflies that feed trout, birds and bats. Key species that I experienced regularly in past years, such as night hawks and bats, are diminished substantially—the river is not in good condition.”

The DRA has asked PGE to consider a pilot program in which it would return to releasing as much cold, clear water from the bottom of the reservoir as possible. The organization points to an independent study PGE commissioned in 2021 that found such an approach promised the best results.

But PGE’s Hill says that’s a nonstarter: “Our modeling shows it wouldn’t make any difference.”

As Oregon races toward eliminating net greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, new data centers are projected to drive electricity demand sharply higher. That means the Deschutes River dams’ importance—and value—will only grow. Oregonians who benefit from reduced emissions, including PGE’s customers, will contribute to the continued degradation of the Deschutes.

State Rep. Emerson Levy (D-Bend), whose district includes a long stretch of the Deschutes, says it’s important that the river not become an unintended casualty.

“The lower Deschutes River is incredibly important to our region,” Levy says. “There are multiple factors stressing the river, including the tower, and as a state, we are a steward of our lands and waters.”

The Littleleafs welcome such interest. They say if state officials were looking out for the river and the public good rather than bowing to the state’s largest utility, they would protect one of the tribe’s—and Oregon’s—greatest resources. And, they say, PGE’s relationship with the people of the Warm Springs Reservation is all too familiar.

“It’s all about the money,” says Elke Littleleaf, the Native fishing guide. “These guys have just used us for our resources.”

Sidebar: The Public Utility Commission

In previous media coverage of the selective water withdrawal tower, little attention has been paid to finances. But money is at the heart of the deal.

Before it installed the tower, Portland General Electric needed approval from the Oregon Public Utility Commission. That agency, with 135 employees and an annual budget of $59 million, is supposed to ensure that Oregonians “have access to safe, reliable and fairly priced utility services that advance state policy and promote the public interest.”

Utilities are highly regulated: In exchange for providing service, they get geographic monopolies and virtually guaranteed profits. The way that works is, they propose investments and, if the PUC finds the investment prudent, it sets rates that allow the utility to recover its costs and earn a handsome profit. (This helps explain why investor Warren Buffett owns the biggest utility west of the Rockies, PacifiCorp.)

Nobody had built a selective water withdrawal tower before PGE did. The novel proposal came with a hefty price tag: $107 million ($156 million in 2024 dollars). In 2008, PGE asked the PUC to greenlight installation of the tower at ratepayer expense and allow the utility a 10.1% annual profit on the tower.

PGE, records show, told regulators that the Deschutes dams have “virtually irreplaceable value to PGE’s system.”

Utilities love dams: The fuel (water) is free; they generate clean, renewable energy; and they act as giant batteries since their generation can be switched on and off easily. That is increasingly useful as utilities transition to wind and solar generation.

“It’s clean power that is dispatchable,” says Bob Jenks of the Citizens’ Utility Board, a watchdog group, “meaning you ramp it up and down very quickly when you need more or less power.”

When PGE asked the PUC for permission to charge ratepayers for the tower, Jenks’ group expressed doubts: The selective water withdrawal tower was unique and untested, and therefore the fish passage portion of the facility might not work. CUB argued that under state law, if PGE invested in any new electrical plant that failed, ratepayers would not have to pay for it.

So, if the tower failed to restore fish runs, ratepayers shouldn’t have to pay for that either, CUB concluded. In separate testimony, PUC staff agreed. “Customers are in the untenable position of having to bear all risks for this project,” staff said.

But the commission, whose three members are appointed by the governor, approved it anyway—with a 95-year depreciation schedule—which means ratepayers will foot the tab for nearly a century regardless of whether the tower works. No annual reviews.

In their final decision, the commission did knock the allowed profit down—from 10.1% to 10%. (The two living commissioners who approved the deal, Lee Beyer and John Savage, say they remember little about it, except that it was a condition of relicensing the dams. “From the standpoint of the ratepayer, we are relying on [the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission] and DEQ to protect the water quality,” Savage says.)

The tower, the PUC reports, currently generates about $6 million a year in profit for its owners. That profit would disappear if PGE took the tower out of service, which gives the utility an incentive to keep it.

“That was a really unusual case,” Jenks says today. “Usually, utilities don’t take risks on unproven technology, but that tower got them their FERC license.”

Rep. Ken Helm (D-Beaverton), who has been fishing and camping on the Deschutes for more than 40 years, says the state can be too deferential to utilities.

“I have many objections to the types of costs that Oregon’s investor-owned utilities are allowed, by law, to pass on to customers—and the cost of the mixing tower is one of them,” Helm says. “The hard truth is that this is not the PUC’s problem because its regulatory function, in this instance, is to protect ratepayers—not fish.”